Private Reuben Roper RMLI

One Day in the Fighting Line

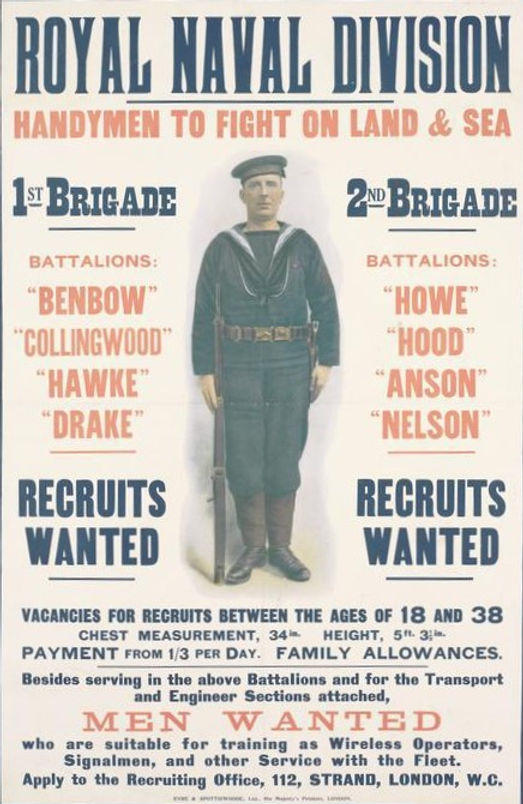

One of the Ansons : this man was in the Anson Battalion, Royal Naval Division

Image: IWM (Art.IWM ART 1342)

Family & Home

Richard and Annie Roper

Reuben was the eldest of seven children born to Richard and Annie (known as Polly) Roper. He was born at Dunhampton Cottage, Hatfield, Hereford on the 8 April 1895. Although he thought he was born on 28 March 1894.

The other children, in order of age, were Thomas, Richard, John, Nellie, Harry and Samuel. The family home was at 34, Rural Vale, Rosherville, Northfleet where eight people lived. They moved here sometime during WW1 probably after Reuben had enlisted in 1916. Richard died here in 1946 and Polly in 1950.

Their father Richard Lottimer Roper was a locomotive train driver and although he originally came from Colchester in Essex because of the nature of his work the family moved around the country a lot. This is reflected in some of the places of birth for the children which are Hereford, Warwickshire, Somerset and Berkshire. Eventually the family settled in Rural Vale, Northfleet, Kent sometime during WW1.

Royal Marine Light Infantry

During WW1 Reuben enlisted for the duration of the war, attesting at Reading on the 28 February 1916 and joining the Royal Marine Light Infantry (RMLI) as Private CH1813/S, he was 21 years old. His trade was given as “holder up” which was a rivet holder. His address at the time of enlisting was 16 Albury Place, Reading. From his medical report it was shown that he was not very tall being only 5’ 3”

He was placed on the Army Reserve until his Mobilization on 30 October 1916 and on the 2 November 1916 he was sent to RMLI Depot at Deal, Kent for basic training. Military life was something that Reuben clearly did not take to straight away as he was soon on report. On his company conduct sheet it is noted that he was “Absent over leave from midnight on 31 January until 4pm on the 1 February 1917” and was admonished with a forfeit of one-day pay.

To France - Briefly

After 12 weeks basic training he was sent to France and arrived at Base Depot in Calais on the 16 February 1917. On the 11 March 1917 he joined the 2nd Royal Marine Battalion (2/RMLI) in the back areas of the Somme sector at either Bouzincourt where “A” and “D” Companies were in billets for working parties on roads and ammunition dumps or with “B” and “C” Companies who were at Puchevillers doing the same.

Within a few days Reuben became ill and reported to the Casualty Clearing Station on the 15 March 1917 and from here he was quickly sent to the 24th General Hospital at Etaples on the 18 March suffering from dysentery.

This became so bad that he was returned to England on the Hospital Ship “Brighton” on the 29 April 1917 and he was later transferred to the 1st Scottish General Hospital in Aberdeen on the 1 May 1917.

Reuben remained here for four months recovering and was then given six days leave from the 8 – 13 September. Yet again he decided that he was not going to follow Army rules and was reported as “Absent over draft leave from 11pm 13 September until 11pm 18 September” and earning him six days “Field punishment No.2” and a forfeit of six days pay in addition.

Back to France - Moving up the Line

Reuben was drafted to 2/RMLI on the 24 September 1917 and left Folkestone on the 25 September arriving back in France at Boulogne and from here he was posted to Base Depot at Calais on the 26 September 1917.

Reuben eventually re-joined 2/RMLI in a draft of 73 other ranks on the 4 October 1917 at “Brown camp” where they soon received orders to move to the Nouveau Monde area just outside the village of Herzeele 20 miles behind the lines on the Ypres front. Here they carried out training using specially constructed trenches to prepare for the up-coming attack as part of the Royal Naval Division in support of the Canadian Corps assault on Passchendaele village.

Training began in earnest on the 8 October and carried on until 22nd when orders were issued informing them to move the next day to the Canal Bank area taking over Reigersburg Camp in the village of Vlamertinghe just behind Ypres town.

On the 24 October they were ordered to proceed by route march the 3½ miles to Irish Farm, a place to the North-West of Ypres town, as part of the 188th Brigade Reserve. This new position was just 4½ miles behind the Front-line and well within range of the German artillery.

The Salient was a dead loss. I cannot think how the one or two senior officers there who had brains let the thing go on. Of course, they were helping the French out which makes a big difference. One doesn’t know what the higher strategy was. But from the tactical side it was sheer murder. You had this Ypres-Yser Canal and you got the strangest feeling when you crossed it. You’d almost abandon hope. And as you got further out you got this awful smell of death. You could literally smell it. It was just a complete abomination of desolation. I wept when I came into the Salient.

2nd Lt. H. L. Birke, Tank Corps

Third Battle of Ypres

The Royal Naval Division (RND) attack planned for 26 October 1917 was part of an ongoing larger battle that had begun on 31 July 1917 officially titled the Third Battle of Ypres but more commonly known as Passchendaele.

When the battle began the objective was to make a breakthrough on the Ypres sector that the British had held since the Autumn of 1914. This was to drive forward and push the Germans back to deny them the use of their railhead at Roulers and to capture the Belgian coast-line and stop U-Boat attacks being launched from this area. It was also decided to launch this attack in support of the French Army that at the time was suffering from several mutinies in its Armies and had effectively ceased to be an offensive fighting unit due to the poor morale.

After a gruelling fight by the British Fifth Army that had lasted throughout the summer and into autumn it became more and more obvious that the plan had to be drastically scaled back. As winter approached, Passchendaele village which stood at the top of the main ridge surrounding Ypres Town, remained in German hands. It was decided that this would be the final objective of the campaign.

This was to be attacked by the Canadian Corps using “bite and hold” tactics with fresh units being allocated specific limited objectives for each phase of the attack. The RND as a part of XVIII Corps would assist the attack from positions just to the North of the 3rd Canadian Division with the 188th Brigade the first into the line for the initial operation beginning on 26 October.

Map showing movement of the Frontline from 31 July - 26 November 1917

63rd Royal Naval Division

188th Brigade

1st Battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry (1/RMLI)

2nd Battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry (2/RMLI)

Anson Battalion (Anson)

Howe Battalion (Howe)

188th Machine Gun Company (188/MGC)

188th Trench Mortar Battery (188/TMB)

Support Troops:

189th Brigade

Hood Battalion (Hood)

Hawke Battalion (Hawke)

190th Machine Gun Company (190/MGC)

Divisional Troops

223rd Machine Gun Company (223/MGC)

What Front-line?

The line to be taken over by the RND ran from a position near Beek Houses, which was next to the Lekkerboterbeek stream then running South-East to Wallemolen Cemetery.

The 173rd Brigade of the 58th Division was on the left flank and the 8th Brigade of 3rd Canadian Division on the right flank.

At 5.00 pm on the evening of the 25 October 2/RMLI moved up to the Front-line along the Alberta Track duckboard to take up its holding position as the Second wave of the attack. This was carried out in Company order with HQ leading the way followed by “A”, “B”, “C” & “D” with Platoons moving at 50 yard intervals the total distance was roughly 5 miles.

188th Brigade positions for the attack 26 October 1917

Going up to the line for the first time my first indication of the horrors to come appeared as a small lump on the side of the duck-board. I glanced at it, as I went past and I saw to my horror, that it was a human hand gripping the side of the track – no trace of the owner, just a glimpse of a muddy wrist and a piece of sleeve sticking out of the mud. After that there were bodies every few yards. Some lying face down in the mud; others showing by the expression fixed on their faces the sort of effort they had made to get back onto the track. Sometimes you could actually see blood seeping up from underneath. I saw the dead where ever I looked – a dead Signaller clinging to a basket cage with two dead pigeons in it, and further on, lying just off the track, two stretcher-bearers with a dead man on a stretcher.

There were the remains of a ration party that had been blown off the track. I remember seeing an arm, still holding on to a water container. When the dead men were just muddy mounds by the track side it was not so bad – they were somehow impersonal. But what was unendurable were the bodies with upturned faces. Sometimes the eyes were gone and the faces were like skulls with the lips drawn back, as if they were looking at you with terrible amusement. Mercifully, most of the those dreadful eyes were closed.

Major George Wade, Machine Gun Corps

Prepartion for Attack

The effort to reach the Front-line was immense and took all evening, with the rain beginning to fall steadily from midnight. All Battalions of the 188th Brigade had completed the relief of the 28th Infantry Brigade without incident and were in position by 2.00 am.

Due to the regular enemy morning barrage being something of a habit and falling some 150-200 yards to the rear of our Front-line it was decided that the forming up positions and jumping off point selected would be 50-100 yards in front of the line held.

2/RMLI were to initially assemble on a line running parallel some 150 yards to the East of the road that ran from Burns House to Vacher Farm. “A” Company were on the right and “C” Company on the left each with two Platoons in the Front-line and two Platoons supporting. “B” Company was the Battalion Reserve positioned immediately to the rear of “A” & “C” Companies and “D” Company had been allocated for carrying supplies. Two Platoons from each Company had been tasked with stretcher-bearer duty due to the extreme conditions of the terrain.

RMLI Battalions assembly positions from approximately 2.00am on the night 25/26 October

The Country resembles a sewage heap more than anything else, pitted with shell-holes of every conceivable size, and filled to the brim with green, slimy water, above which a blackened arm or leg might project. It becomes a matter of great skill picking a way across such a network of death-traps, for drowning is almost certain in one of them.

Private Hugh Quigley, Lothian Regiment

Front-line and communication trenches were non-existent, the forward system consisted of isolated posts with a sea of mud between them, scattered in depth over a wide area with each being dependent on their own defensive protection. The support line was the same with the occasional ruined farm house, out-building or captured German concrete pill-box employed as Company Headquarters.

Enemy posts were often positioned between these scattered defensive posts and those providing rations and support often had to fight their way forward to supply these outposts. Communications and therefore organisation was extremely difficult under these conditions and as a result this would have consequences of its own during the attack.

16th Canadian Machine Gun Company

Library and Archives Canada

No Escape

All supplies and reinforcements had to be brought up on duck-board or corduroy tracks laid across this wasteland. If a soldier wandered off these tracks they would be plunged into a waist-deep slurry of filth where the rotting bodies from three years of fighting were mingled with mud and slime from continuous shelling. To fall into this hell would often mean death. Because the enemy had clear lines of sight and knew every inch of these tracks, movement along them was only possible at night. If an accurate bombardment landed during use there could be no escape.

The 188th Brigade had taken over the line just before the battle as no unit could hold these positions for any length of time and still be fresh enough for the arduous task of assaulting the enemy positions.

Australians on duckboard track at Passchendaele

Enemy Strong Points

The plan of the attack was for separate and self-supporting units to attack limited and specific targets with no other objectives. Once they had achieved their target they were to take no further part in the attack - this would prove to be an ineffective tactic and would quickly change.

One of the chief tactical features on the intended front of attack was the Paddebeek stream which ran parallel to our front at a distance of about five hundred yards. Beyond the Paddebeek and to the right on higher ground was the fortified ruin of Tournant Farm and Source Farm these commanded clear views over the flat terrain that the British Front occupied.

Mile after mile the earth stretched out black, foul, putrescent. Like a sea of excrement…. It was one vast scrap-heap. And, scattered over or sunk in the refuse and mud, were the rotting bodies of men, of horses and mules. Of such material was the barren waste that stretched as far as the eye could see.

Robert Briffault

From the vantage point of Passchendaele ridge the Germans had a clear observation over the entire British Lines all the way to Ypres town and beyond. They could see any troop movements and bring artillery fire to bear down on those caught in the open.

Along with the concrete Pill-boxes manned with machine-guns the German defenders employed effective snipers in these bunkers and in shell-holes across the battlefield.

German Strong-points across the Paddebeek

An Impossible Task

The First-wave had Anson on the right, with a front of around 600 yards, which would attack Varlet Farm, Source Trench and the fortified shell-holes on the Divisional boundary and the 1/RMLI on the left, with a front of 900 yards, would assault Berks Houses, Bray Farm and Banff House.

The Second-wave objectives comprised Tournant Farm and Source Farm on the right which Howe would assault after passing through Ansom.

The 2/RMLI on the left as part of the Second-wave would advance through 1/RMLI and assault Sourd Farm then cross the Paddebeek stream and attack the concrete pill-box 300 yards beyond. The furthest objective was 1400 yards from the British Front-line an impossible distance in the strength sapping mud of Flanders.

Each man was to be dressed in full Battle Order without Great coat. Instead, they had been issued with leather jerkins and as the weather was bitterly cold this was desperately needed. The gas mask was to be worn in the emergency position on the front of the chest. Additional to the normal equipment were two days rations with emergency rations, 220 rounds of Small Arms Ammunition (S.A.A.), two sand bags and a hand-grenade. On top of this was a tin helmet and rifle. Every third man was detailed to carry a shovel or rifle grenade; altogether a very heavy burden for each soldier.

First Wave attack objectives 26 October 1917

Second Wave attack objectives 26 October 1917

"The Word Retire Does Not Exist"

Zero hour was set for 5.40am 26 October 1917 and just before this 2/RMLI were to move up behind 1/RMLI; about 200 yards from their current position . This jumping off point was just in front of the original British Front-line and they were to stay in this position until the designated time for the Second-wave attack at 6.30am.

Brigadier General Robert Prentice had issued specific instructions for the attack down to the last detail including a word of caution – “All ranks are to be warned that the word ‘Retire’ does not exist” – it was clear that the men of the RND were expected to prove their valour.

The British bombardment began on time with the rain pouring down in torrents and the sky still dark – sunrise would not be until 7.26am. The enemy opened retaliatory fire about three minutes later but just as expected this fell behind the assembly line for the most part.

2/RMLI holding position after Zero Hour 5.40am until 6.30am

The Terror of Waiting

Most of my boys were young Londoners, just eighteen or nineteen, and a lot of them were going into a fight for the first time. Regularly during the night I crawled round to check on my scattered sections, having a word here and there and trying to keep their spirits up.

The stench was horrible, for the bodies were not corpses in the normal sense. With all the shell-fire and bombardments they’d become continually disturbed, and the whole place was a mess of filth and slime and bones and decomposing bits of flesh.

Everyone was on edge and as I crawled up to one shell-hole I could hear a boy sobbing and crying. He was crying for his mother. It was pathetic really, he just kept saying over and over again, “Oh, Mum! Oh, Mum!” Nothing would make him shut up, and while it wasn’t likely that the Germans could hear, it was quite obvious that when there were lulls in the shell-fire the men in shell-holes on either side would hear this lad and possibly be affected. Depression, even panic, can spread quite easily in a situation like that. So I crawled into the shell-hole and asked Corporal Merton what was going on. He said, “It's his first time in the line, sir.

I can’t keep him quiet, and he’s making the other lads jittery.” Well, the other boys in the shell-hole obviously were jittery and, as one of them put it more succinctly, ”fed up with his bleedin’ noise”. Then they all joined in, “Send him down the line and home to Mum” - “Give him a clout and knock him out” - “Tell him to put a sock in it, sir.”

I tried to reason with the boy, but the more I talked to him the more distraught he became, until he was almost screaming. “I can’t stay here! Let me go! I want my Mum!”

So I switched my tactics, called him a coward, threatened him with court-martial, and when that didn’t work I simply pulled him towards me and slapped his face as hard as I could, several times. It had an extraordinary effect. There was absolute silence in the shell-hole and then the corporal, who was a much older man, said, “I think I can manage him now, sir.”

Well, he took that boy in his arms, just as if he was a small child, and when I crawled back a little later to see if all was well, they were both lying there asleep and the corporal still had his arms round the boy - mud, accoutrements and all. At zero hour they went over together.

Lt. A. Angel - 2/4th London Bn, Royal Fusiliers, 58th Division

Support Units

Trench Mortars

Two Trench Mortars had been allotted to each attacking Battalion with their fire concentrated on Varlet Farm on the right flank and Berks Houses on the left. They managed to complete their support fire but owing to the difficult nature of the ground were unable to assist in moving forward.

Machine Guns

188th, 190th and 223rd MGC were to provide a machine-gun barrage in support of the attack with 4 sections on the right and 6 sections allocated to the left flank making a total of 40 machine-guns firing up to 3,000 rounds per hour; each sending a deadly hail of bullets into areas occupied by the enemy.

188th Machine Gun Company were to provide 2 sections to attack along with the ground troops one for each flank a total of 8 machine-guns.

First-wave

As the First-wave set off despite the difficult conditions they managed in the most to keep up with the barrage which moved forward at a rate of 100 yards every 8 minutes. By 6.59am the Ansom on the right had seen some success with 50 prisoners taken and by 7.20am Varlet Farm reported as captured; this was a case of mistaken identification. The position actually occupied by Ansom was about 200 yards to the East of Varlet Farm.

On the left 1/RMLI had gained their first objective Berks Houses by 7.30am and after some stiff fighting had completed the capture of their last position Banff House by 8.25am.

First wave objectives and progress

Second-wave - Right Flank

As planned Howe passed through Ansom and on the extreme right of the attack “C” Company met with heavy casualties just South of Source Trench during this advance. By 9.00am a few small parties had reached the Paddebeek, they crossed this small stream advancing on Source Farm and Tournant Farm becoming mixed up with the Canadians attacking on the right but eventually having to fall back with the Canadians.

Howe’s left Company “D” and some of “A” had advanced past Varlet Farm but then became mixed up with Ansom who had been held up in front of them.

Second-wave - Right Flank attack progress

Second-wave - Left Flank

2/RMLI had waited patiently for 50 minutes on their jumping off point and at 6.30am advanced with “C” Company on the left moving up to 1/RMLI positions in the vicinity of Berks House and Bray Farm. From here they were supposed to wait for the barrage and then to pass through the 1/RMLI positions and continue the Second-wave attack.

“C” Company’s objectives were to assault five organised shell-holes and another group of eight shell-holes just 100 yards to the North-East of Banff House which was held by 1/RMLI.

The barrage intended to assist the Second-wave advance had been scheduled for 7.36am but due to the hold up of the First-wave this barrage had already passed by the time the Second-wave troops were in position and therefore the 2/RMLI would have to attack without this protection

Second-wave - Left Flank attack progress

Murderous Machine Gun Fire

Owing to the desolate terrain, with often only enemy concrete Pill-boxes the only obvious visible landmarks, to attack without a barrage was an impossible task. To rush such positions required the defenders manning these garrisons to be seeking shelter from our artillery barrage and the assaulting troops to be close to the barrage.

Even then the conditions of the ground made for extremely slow progress for the assaulting troops. To attack these positions, across open terrain with only shell-holes for cover and the enemy garrisons able to bring Machine-gun and rifle fire onto the attackers, was virtually suicide.

Machine-gun fire from a strong-point across the Lekkerboterbeek and from a Pill-Box about 300 yards to the North held up both 1/RMLI and 2/RMLI in the vicinity of Berks Houses, Bray Farm and Banff House.

Map showing the positions on the left flank where the attack is held up by machine-guns in concrete Pill-boxes

Across the Paddebeek

“A” Company 2/RMLI on the right hand flank of the Battalion front had passed through 1/RMLI by 9.00am and began their attack. The leading Platoons of “A” Company had reached the line of the Paddebeek and crossed it to the South East of Sourd Farm – another one of their objectives but which remained in the hands of the enemy and would not be taken until the night of 3/4 November by another Battalion of the Brigade. A great number of men were killed crossing the stream and numerous bodies were left lying along the line of it.

A representation of British battle casualties

Centre of the Attack

In the centre of the attack it was reported at 11.00am that a mixed party of Royal Marines was held up in a position just to the West of Varlet Farm by the enemy who were holding a Bank about 100 yards to the East and had been enfilading our positions. Instructions were issued from Battalion HQ for these men to push on with the attack and runners were sent out to try and make contact but all of these had returned without finding them.

Even in daylight it was extremely difficult to orientate yourself especially amongst the shelling and continuous fire from the numerous fortified bunkers and redoubts. These were positioned so as to provide covering cross-fire for each defensive position and as the defenders also occupied the heights surrounding the area they were able to fire over open sights with their artillery at any sign of movement in front of them.

“B” Company 2/RMLI

An officer of 2/RMLI went forward and at 12.50pm reported that a party of “B” Company was holding Banff Houses and the positions just in front with the enemy to the North and North-West.

By 3.30pm the General Officer Commanding the Division Major-General C. E. Lawrie arrived and after assessing the situation approved of the artillery barrage being brought back to a line of protection just in front of the first objective – this meant that those who had crossed the Paddebeek would be subjected to our own shell-fire.

“A” Company 2/RMLI

Across the Paddebeek there was only one objective to obtain, this being a concrete pill-box about 300 yards to the North-West. The attack by “A” Company and led by Captain Ligertwood had gone into action under their own Platoon flags which were strips of red canvas nailed to sticks and solemnly blessed by the Battalion Chaplain in lieu of Regimental Colours.

In support of “A” Company 2 guns of No.4 Section 188/MGC had also crossed the Paddebeek and gave valuable assistance to the attack. Captain Ligertwood, wounded three times, led his Company to within site of the goal when he fell mortally wounded a fourth time; raising his head he pointed towards the target and urged his men onwards.

This small group of men fought on in desperate conditions becoming surrounded by the enemy. Eventually exhausted and isolated having run out of ammunition or their weapons had ceased to work due to the ubiquitous mud they finally retreated at dusk. As they fell back on Burns House many were killed trying to cross the Paddebeek again.

Isolated Garrisons - Holding On

The fighting had lasted all day and as evening approached a mixed group of around 100 men of 1/RMLI and 2/RMLI were occupying Berks House, Bray Farm and Banff House along with some positions just to the South.

Around about 5.45pm as dusk arrived a heavy barrage forced these small garrisons out of their positions and soon only Berks House remained in our hands.

It is probable that due to the isolation of each of these small garrisons, along with the lack of clear communication and support, that the soldiers in these positions seeing the remnants of “A” Company retreat back across the Paddebeek thought that this was a general retreat and fell back so that they would not be left isolated and exposed.

Orders were sent forward that Bray Farm and Banff House were to be re-taken that night. This was only partially achieved by a Platoon led by a Sergeant who managed to occupy a line just West of Bray Farm, and by a few men under a Corporal who held out in some shell-holes 50 yards North East of Bray Farm.

No Hope for the Wounded

Two Platoons from each Company had been allocated as Stretcher Bearers owing to the extreme difficulty in moving any of the wounded men from the battlefield. Most of those badly wounded would die in water-filled shell-holes unable to be rescued by their comrades.

From the darkness on all sides came the groans and wails of wounded men; faint, long, sobbing moans of agony, and despairing shrieks. It was too horribly obvious that dozens of men with serious wounds must have crawled for safety into new shell-holes, and now the water was rising about them and, powerless to move, they were slowly drowning.

2/Lt Edwin Campion Vaughn MC, 8th Warwicks

A team of stretcher bearers struggle through deep mud to carry a wounded man to safety near Boesinghe on 1 August 1917 during the Third Battle of Ypres. Imperial War Museum Q5935

Hell for the Living

Some called out to their comrades for help, trusting their pals would find them, but these wounded men were alone amongst the dead in the inky blackness. Those who survived unscathed had to endure these dreadful sounds, impotent to be able to do anything to help them, some men wept and all were affected by the piteous cries.

The cries of the wounded had much diminished now, and as we staggered down the road, the reason was only too apparent, for the water was right over the tops of the shell-holes. From survivors there still came faint cries and loud curses. When we reached the line where the attack had broken we were surrounded by the men who earlier had cheered us on. Now they lay groaning and blaspheming, and often we stopped to drag them up on to the ridges of earth. We lied to them all that the stretcher-bearers were coming, and most resigned themselves to a further agony of waiting. Some cursed us for leaving them, and one poor fellow clutched my leg, and screaming ‘Leave me, would you? You Bastard!’ he dragged me down into the mud. His legs were shattered and when Coleridge pulled his arms apart, he rolled towards his rifle, swearing he would shoot us. We took his rifle away and then continued to drag fellows out as we slowly proceeded towards HQ.

2/Lt Edwin Campion Vaughn MC, 8th Warwicks

Exhausted

Rain fell less harshly the next day 27 October and the shelling was less intense as the desolate troops clung on to the precarious gains of the day before and consolidated their positions as best as possible. From the two battalions of RMLI that began the attack there remained half a Company that was situated about 100 yards East of Vacher Farm a little behind our original Front-line.

One Platoon was in a concrete pill-box at Shaft to the West of Berks Houses where half a Company were in occupation. One Platoon was at Bray Farm and one Company was in a defensive line facing Eastward to the South of this position.

By the evening of the 27 October the men were completely exhausted and Brigadier General Prentice decided to relieve Ansom and Howe with Hood on the right-flank just in time to stop a German counter-attack from regaining all the positions that had been so hard won during the previous day.

On the left Drake was sent forward to relieve the Royal Marines and they managed to re-take the garrisons lost in the retreat at dusk the night before so that by the end of the two days fighting a meagre gain of some 300-400 yards had been made from our original lines. A pitiful gain for such a heavy loss.

Final Line - 27 October after two days of fighting

A Heavy Price

Of the 16 officers and 597 other ranks from 1/RMLI that started the battle the casualties were 11 officers and 270 other ranks. 2/RMLI would suffer casualties of 7 officers and 301 other ranks among them was 21 year Private Reuben Roper in his first and last battle.

Reuben’s body was never identified or recovered and so he is listed on panel 1 of the Tyne Cot Memorial wall to the missing. The memorial commemorates 34,990 men who died and are listed as missing between August 1917 and November 1918 in the Ypres salient.

In the following few days those taking over the line would change tactics from open assaults in daylight to develop night attacks. These would involve moving small groups of men forward in darkness to get close enough to the concrete Pill-boxes and then using the cover of darkness they would rush these positions and using grenades and bayonets either kill or take the defending Garrisons prisoner.

In this way the objectives that had eluded the attackers on the 26 October had all been achieved by the 5 November at the cost of 14 killed and 148 wounded; allowing for the final push to be carried out to take the village of Passchendaele by the Canadians.

The Second Battle of Passchendaele that had begun on the 26 October finished on the 10 November 1917.

One Day in the Fighting Line

Killed in Action on the 26 October 1917

195 Royal Marines

-

1/RMLI had 97 men killed - 89 of these have no known grave.

-

2/RMLI had 98 men killed - 82 of these have no known grave.

Others would die later from their wounds - in total 215 men of the RMLI would die between 25-31 October 1917

The 63rd Royal Naval Division had 3,126 casualties, killed, wounded and missing from 26–31 October

The British Official History recorded a total of 244,897 British Empire casualties killed, wounded and missing, during the offensive. Recent estimates suggest a higher total, thought to have been around 275,000. While the French Army suffered around 8,500 casualties, German losses remain controversial. Estimates range from 217,000 to around 260,000.

Telegram

At some point in November 1917 the dreaded telegram would have been delivered to 34 Rural Vale, just one more in the small road to another grieving family, this time the Ropers. Polly was listed as the next-of-kin on Reuben’s service papers.

After the war had finished the Government issued medals to those who had taken part and Reuben was entitled to the British War Medal and Victory Medal as shown on his records these would have been issued to his next-of-kin along with the Memorial Plaque and Scroll.

Reuben is commemorated on Tyne Cot Memorial to the missing and Northfleet War Memorial.

Panel 1 Tyne Cot Memorial

Commemorative wreath laid 26 October 2007

Northfleet War Memorial in it's original position

References

63rd Royal Naval Division Headquarters Branch and Services:

General Staff WO95/3095 1917 Oct – 1918 Feb

ADM137/3931 – 63rd Division report for the attack Oct 24 – Nov 5

WO95/3110/27940 – Operation Orders No. 91 – 25 October 1917

Orders for the attack commencing 26 Oct 1917 by 2 RMLI

W095/3108/10457 – Report by Brigadier General commanding 188th Infantry Brigade

dated 31 Oct 1917 in connection with the attack on 26 Oct 1917

the report is added to on 10 Nov 1917

188th Brigade – WO95/3110

Brigade Headquarters WO95/3108/2

1 RMLI – WO95/3110/1

2 RMLI – WO95/3110/2

Anson Battalion – WO95/3111/1

Howe Battalion – WO95/3111/2

188th Machine Gun Company – WO95/3111/4

188th Trench Mortar Battery – WO95/3111/5

Support troops

189th Brigade Headquarters – WO95/3112

Hood Battalion – WO95/3115/1

Hawke Battalion – WO95/3114/2

Divisional troops

223rd Machine Gun Company

To the left (next to 2 RMLI) of the attack was the

2/2nd Battalion London Regiment – WO95/3001/4

2/3rd Battalion London Regiment – WO95/3001/7

173rd Brigade, 58th Division

To the right of the attack was the

4th Battalion Canadian Mounted Rifles – WO95/387

28th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division

8th Canadian Brigade Headquarters – WO95/3868

Reuben Roper Personal papers

ADM159/146 – Enlistment papers for Reuben also Attestation papers

ADM242/10 – Register of deaths

ADM171/169-170 – Medal entitlement

Maps

Sheet 28 NE

Sheet 20 SE

Books

Command in the RND – Christopher Page p.154-161

a description of Brigadier-General Asquith - commander of 189th Brigade at the battle

The Royal Naval Division - Douglas Jerrold p.249-260

“Britain’s Sea Soldiers” A Record of the Royal Marines

during the War of 1914-1919 – H.E. Blumberg

p.332 – 336 description of the attack by RND

Some Desperate Glory - Edwin Campion Vaughn MC

They Called it Passchendaele - Lyn Macdonald

Passchendaele - Battleground Europe - Nigel Cave

Uncovering the Story of Reuben Roper

Despite Reuben Roper coming from the Rosherville parish in Northfleet, his name is not listed on the Rosherville War Memorial. Even more surprisingly, he is also absent from the published list of names associated with the Northfleet War Memorial, which was printed in the local newspaper at the time of its unveiling in 1923.

When I began tracing my family history in 1999, I asked my Nan, Kathleen—who had married Reuben's brother John, my grandfather—about Reuben. She remembered that, “he had joined the Army and was killed in the Great War and his name was on the Memorial at Northfleet.”

I contacted the church outside which the Northfleet memorial stands, as well as the Royal British Legion and the local council, but none of them could provide a list of the names commemorated. Reuben’s absence from all official local records was baffling.

After extensive searching—initially in the Army records—I was finally directed by a helpful person online to look instead under the Royal Navy, as Reuben was not in the Army but in fact a Royal Marine. A simple search of the CWGC database confirmed it. A later visit to the National Archives at Kew revealed his full service record, which allowed me to uncover what happened to Reuben and the other men of the 2nd Battalion Royal Marines at Passchendaele.

Andrew Marshall